By: Aaron Bertrand | Updated: 2019-06-18 | Comments (6) | Related: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | > Locking and Blocking

Problem

A whole category of performance problems in SQL Server finds its roots in the fact that, under the default isolation level, writers block readers. The READ UNCOMMITTED isolation level – also known as NOLOCK – is a common, though fundamentally flawed, approach to addressing this scenario.

Solution

There are several downsides to NOLOCK, and they are well-publicized, but I find they are often ignored by people who haven't experienced the issues first-hand. In this tip, I demonstrate a few different cases where the semantics around reading uncommitted data leads to incorrect results.

Skipping and Double-Counting Rows when using SQL Server NOLOCK

The first two problems, which are relatively easy to demonstrate, involve the way scans are performed under read uncommitted isolation. Specifically, if a row is moved to a new page, it can be counted twice, or not counted at all. The simplest way to demonstrate this is to cause page splits while a COUNT operation is being performed. We can start with the following simple table with 100,000 rows:

DROP TABLE IF EXISTS dbo.Largish; CREATE TABLE dbo.Largish ( id int IDENTITY(1,1), filler char(512), gooid uniqueidentifier NOT NULL DEFAULT NEWID(), CONSTRAINT pk_largish PRIMARY KEY CLUSTERED(gooid) ); GO INSERT dbo.Largish(filler) SELECT TOP(100000) LEFT(s1.[name],10) FROM sys.all_objects AS s1 CROSS JOIN sys.all_columns AS s2;

In one window:

DECLARE @double int = 0, @skipped int = 0, @proper_count int, @delta int;

SELECT @proper_count = COUNT(*) FROM dbo.Largish;

WHILE @double + @skipped < 2

BEGIN

SELECT @delta = COUNT(*) - @proper_count FROM dbo.Largish WITH(NOLOCK);

IF @delta <> 0

BEGIN

IF @delta < 0

BEGIN

PRINT 'Skipped rows: ' + CONVERT(varchar(6), ABS(@delta));

SET @skipped = 1;

END

ELSE

BEGIN

PRINT 'Double-counted rows: ' + CONVERT(varchar(6), ABS(@delta));

SET @double = 1;

END

END

END

Then, in a second window, run this update in a loop:

SET NOCOUNT ON; WAITFOR DELAY '00:00:00.500'; UPDATE dbo.Largish SET gooid = NEWID() WHERE id = CONVERT(int,(RAND()*99999)+1); GO 100

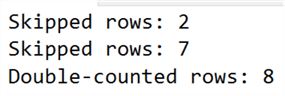

Now, switch back to the first window, and watch the Messages pane for any output from the conditionals. The loop here will stop running as soon as there is at least one instance of missing rows and at least one instance of double-counting rows. Within a few seconds, this was my output:

We're not adding or removing rows here; this is just an UPDATE. An UPDATE can't cause the count of rows in the table to change, so the COUNT() operation missed some rows (because a not-yet-read page was moved to an already-read point in the scan, or double-counted some rows (because a previously-read page was moved to a not-yet-read point in the scan). Note that COUNT() is the easiest way to demonstrate this, but it could happen with non-aggregate operations, too. Seeing a row repeated, or identifying a row that is missing, in a Management Studio grid containing around 100,000 or so rows is a little tougher.

The simple explanation here is that READ UNCOMMITTED does not force the scan to correct for data that has moved during the operation (in fact sometimes you get an error, Msg 601, when this movement has been detected).

Returning Corrupted Data when using SQL Server NOLOCK

There is another troubling symptom resulting from NOLOCK queries, and while it is similar to the above example, it is potentially far more dangerous. This time we can create a simple, one-row table, and populate the LOB columns with a large enough string that pushes the data onto multiple pages for both columns:

DROP TABLE IF EXISTS dbo.SingleRow;

CREATE TABLE dbo.SingleRow

(

RowID int NOT NULL,

LOB1 varchar(max) NOT NULL,

LOB2 varchar(max) NOT NULL,

CONSTRAINT pk_SingleRow PRIMARY KEY CLUSTERED(RowID)

);

INSERT dbo.SingleRow(RowID,LOB1,LOB2) VALUES(1,

REPLICATE(CONVERT(varchar(max),'X'),16100),

REPLICATE(CONVERT(varchar(max),'X'),16100));

In one session, run the following UPDATE in a loop. All this does is repeatedly update the data in these columns to alternately be XXXXX… or YYYYY…

SET NOCOUNT ON;

DECLARE @AllXs varchar(max) = REPLICATE(CONVERT(varchar(max), 'X'), 16100),

@AllYs varchar(max) = REPLICATE(CONVERT(varchar(max), 'Y'), 16100);

WHILE 1 = 1

BEGIN

UPDATE dbo.SingleRow

SET LOB1 = @AllYs, LOB2 = @AllYs

WHERE RowID = 1;

UPDATE dbo.SingleRow

SET LOB1 = @AllXs, @LOB2 = @AllXs

WHERE RowID = 1;

END;

In a second session, read the values with NOLOCK to see if there are any scenarios where the two values in a row don't match, or the value in a column isn't all X or all Y (both of which should not be possible).

DECLARE @bad_row int = 0,

@bad_tuple int = 0,

@LOB1 varchar(max) = '',

@LOB2 varchar(max) = '',

@AllXs varchar(max) = REPLICATE(CONVERT(varchar(max), 'X'), 16100),

@AllYs varchar(max) = REPLICATE( CONVERT(varchar(max), 'Y'), 16100);

WHILE @bad_row + @bad_tuple < 2

BEGIN

SELECT @LOB1 = LOB1, @LOB2 = LOB2

FROM dbo.SingleRow WITH(NOLOCK)

WHERE RowID = 1;

IF @LOB1 <> @LOB2 AND (@LOB1 IN (@AllXs,@AllYs)) AND (@LOB2 IN (@AllXs,@AllYs))

BEGIN

-- corrupt row (one column before an update, one column after update)

SET @bad_row = 1;

PRINT 'Corrupt row. LOB1 = ' + LEFT(@LOB1, 10) + '...' + RIGHT(@LOB1, 10)

+ '..., LOB2 = ' + LEFT(@LOB2, 10) + '...' + RIGHT(@LOB2, 10);

END

IF @LOB1 NOT IN (@AllXs, @AllYs)

BEGIN

-- corrupt tuple (one LOB page from before an update, one LOB page from after)

SET @bad_tuple = 1;

PRINT 'Corrupt value. LOB1 = ' + LEFT(@LOB1, 10) + '...' + RIGHT(@LOB1, 10);

END

END;

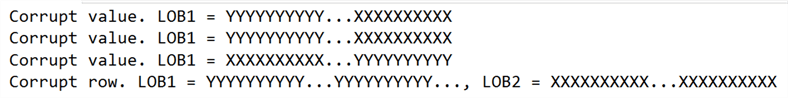

Shortly, you should see output similar to the following:

- NOTE: Don't forget to kill the perpetual UPDATE script.

Now imagine you are pulling large documents, images, or XML, and using NOLOCK to avoid being blocked by write activity against the table. Would you like to print out a resume that has my educational background mixed with Paul White's work experience? That's a bit of an extreme and impractical example, but depending on the data you're trusting to be transactionally consistent within any given row or column, it is certainly possible.

Again, READ UNCOMMITTED does not force the read to confirm that it has the correct pages, all in the right transactional state, corresponding to any given row or even tuple. I want to give full credit to the inspiration behind this example to Paul White, who has written about isolation levels extensively.

Summary

NOLOCK is a tempting way to reduce reader-writer contention in a busy workload, but I have demonstrated here that all kinds of interesting phenomena can happen during read operations that are going to be unacceptable in many scenarios, and even catastrophic in some. Some of these phenomena are possible in other isolation levels too, but to solve the scenario of writers blocking readers, without losing any accuracy you would have only reading committed data, consider READ COMMITTED SNAPSHOT isolation. It's not free, but it's a heck of a lot safer than NOLOCK, since it offers the latest committed version of any row at the time the query began.

Next Steps

Read on for related tips and other resources:

- Demonstrations of Transaction Isolation Levels in SQL Server

- Snapshot Isolation in SQL Server 2005

- Understanding the SQL Server NOLOCK hint

- Bad habits : Putting NOLOCK everywhere

- Concurrency Effects (Microsoft Docs)

- SQL Server Isolation Levels : A Series

- How to implement Snapshot or Read Committed Snapshot Isolation

- How to Choose Between RCSI and Snapshot Isolation Levels

About the author

Aaron Bertrand (@AaronBertrand) is a passionate technologist with industry experience dating back to Classic ASP and SQL Server 6.5. He is editor-in-chief of the performance-related blog, SQLPerformance.com, and also blogs at sqlblog.org.

Aaron Bertrand (@AaronBertrand) is a passionate technologist with industry experience dating back to Classic ASP and SQL Server 6.5. He is editor-in-chief of the performance-related blog, SQLPerformance.com, and also blogs at sqlblog.org.This author pledges the content of this article is based on professional experience and not AI generated.

View all my tips

Article Last Updated: 2019-06-18