By: Hristo Hristov | Updated: 2022-06-10 | Comments | Related: > Python

Problem

When creating a program, the programmer needs to account for potential errors that may arise during the program's execution. It is often difficult to anticipate all such possible errors, although a scope can be established depending on what function the program fulfills and how it does so (e.g., data type errors).

Solution

Python code offers the try/except clause which enables the developer to design intelligent error handling that "catches" run-time errors. This process enhances the predictability of the program and structures the internal errors that occur. The reasons are manifold but mostly due to either unforeseen inputs or results from the program execution.

Need for Python Exception Handling

The developer must plan methodically and anticipate certain errors during program run-time. An error response based on a built-in exception class better explains what exactly went wrong as compared to a default error message that the interpreter serves. In the Python documentation you can find a handy overview of the class hierarchy for built-in exceptions. For example, here are two common ones that are easy to raise yourself and thus test with:

ZeroDivisionError: raised when the second argument

of a division or modulo division is zero. The associated value is a string indicating

the type of the operands and the operation. For example:

AttributeError: raised when an operation or

a function is applied to an object of a non-compatible type. The associated value

is a string giving details about the type mismatch. For example, performing a math

operation on a string value:

These two errors are just a quick illustration how the interpreter reacts when a part of the program is not (fully) compatible with the rest of the program structure. Considering these two examples, let us investigate how to take advantage of Python's error handling capabilities.

Python Try, Except and Else Clause

The general form of the try statement includes a try clause, an except clause and an optional else clause. See the following example:

try: # block of code except SomeError: # handles specific errors except SomeOtherError: except (SomeError, SomeOtherError, YetAnotherError) # runs if any of these occur except: # handles any error that may arise else: # ELSE BLOCK - code under this clause is executed if no exception occurred.

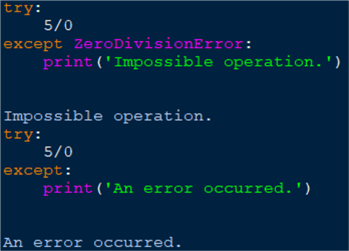

The try block contains the code being "screened" for potential errors. That is probably the biggest caveat of error handling: you need to determine and implement which part of the program to wrap with a try clause. Therefore, your code may be structured in a way suitable for try/except wrapping. After the try clause, we can have one or many except clauses that define the program's behavior upon encountering the specific error. There are two ways to write the statement here: either handle any error by using the except clause without an exception class or pass one or more specific exception classes. This approach largely depends on the program. I would recommend being specific and mention the errors you expect your program may throw. Let us compare the following code:

try:

5/0

except ZeroDivisionError:

print('Impossible operation.')

#

try:

5/0

except:

print('An error occurred.')

Here we are producing one and the same error. The only difference is that in the first try/except block we mention the expected error specifically, while in the second block, we have only the except keyword without specifying the possible error. The outcome is the same in this case.

The optional else clause

Let us see how to take advantage of the optional else

clause. Everything under it will execute when no error has been raised:

numerator = 5

denominator = 1

result = 0

try:

result = numerator/denominator

except ZeroDivisionError:

print('Can\'t divide by zero!')

else:

print(result)

If it was a real program, then the value for the denominator could have been either a wrong value (such as 0) or even the wrong data type (such as string).

Python Try, Except, Else and Finally Block

The finally clause can appear always after the

else clause. It does not change the behavior of the

try/except block itself, however, the code under finally will be executed in all

situations, regardless of if an exception occurred and it was handled, or no exception

occurred at all:

try: # block of code except: # error message else: # executed if no exception occurred finally #executed regardless if an exception occurred or not

To illustrate let us expand the previous example:

def attempt_division(numerator, denominator):

try:

result = numerator/denominator

except ZeroDivisionError:

print('Can\'t divide by zero!')

else:

print(result)

finally:

print('operation completed')

The result is the same but with the extra message for operation completion. In

the second case, where there is indeed an exception raised, the exception is handled,

the code under the else clause is skipped and the code under

finally still runs.

Nesting Try and Except Statements

As a rule of thumb, I would recommend avoiding nesting try/except blocks. Nesting per say is not wrong, however, it complicates the structure and makes the code a bit more obfuscated. On the other hand, sticking to "flat" try/except blocks is more straightforward to read and easier to grasp. It is part of Python's philosophy "easier to ask forgiveness than permission", abbreviated as EAFP. This is a clean and fast style of coding. What makes it unique is that it contains many try/except statements. Let us illustrate with an example. First, let us try nesting try/except:

def divide_by(numerator, denominator1, denominator2):

result = 0

try:

result = numerator/denominator1

except ZeroDivisionError:

try:

result = numerator/denominator2

except ZeroDivisionError:

print('zero division error')

else:

print('operation succeeded with d2')

else:

print('operation succeeded with d1')

return result

divide_by(5,0,0)

divide_by(5,0,1)

divide_by(5,1,0)

The example is deliberately convoluted. While we can state the result is as expected, reading the code may be confusing. Also, what if our function had more than two denominators? How would we nest our try/except blocks without explicitly knowing the nesting logic? We can see the improvement in this example:

def divide_by_v2(numerator, denominator1, denominator2):

result = 0

try:

result = numerator/denominator1

except ZeroDivisionError:

print('zero division error with d1')

else:

print('operation succeeded with d1')

try:

result = numerator/denominator2

except ZeroDivisionError:

print('zero division error with d2')

else:

print('operation succeeded with d2')

return result

divide_by_v2(5,0,0)

divide_by_v2(5,0,1)

divide_by_v2(5,1,0)

Here, there are two separate try/except blocks, one for each denominator argument. The output is as expected and clearly follows the structure of the function code definition.

Raise Exceptions

Python also gives you the option to raise custom exceptions. This allows you

to place additional safeguards in your programs by intercepting the control flow

by means of an exception. To do so, use the raise

keyword with a single argument indicating your exception. This must be either an exception instance

or an exception class (a class that derives from Exception

(see beginning of tip). The basic use of raise is

intended to be implemented with or without a try/except block.

def eval_numbers(num1,num2):

if num1 > num2:

raise ValueError('num1 must be greater than num2')

else:

return 'ok'

Calling this function with the wrong arguments raises the

ValueError:

Additionally, there is another use of raise. For

example, let us take a function that sums up two numbers. Let us test the behavior

with and without raise:

def add_numbers():

num1 = input()

num2 = input()

result = 0

try:

result = int(num1) + int(num2)

except ValueError:

print('there was an error')

raise

else:

return result

In the first call, the inputs are integers, so we get a result. In the second

call, the second input is a string. This causes the ValueError.

Further to that, raise took it and raised it again.

In short, raise allows you to re-raise your exception. To compare, here is the same

function without the raise keyword:

This time the error has occurred again, but the exception has been contained inside the except block.

Conclusion

In this Python tutorial, we examined how to handle exceptions with the try/except/else/finally statement and how to raise your own exceptions. With this information you can make your programs "behave" in a more open and understandable way. This way you can adhere as much as possible to the Zen of Python: "Errors should never pass silently. Unless explicitly silenced."

Next Steps

Learn Python Programming Language with Me

About the author

Hristo Hristov is a Data Scientist and Power Platform engineer with more than 12 years of experience. Between 2009 and 2016 he was a web engineering consultant working on projects for local and international clients. Since 2017, he has been working for Atlas Copco Airpower in Flanders, Belgium where he has tackled successfully multiple end-to-end digital transformation challenges. His focus is delivering advanced solutions in the analytics domain with predominantly Azure cloud technologies and Python. Hristo's real passion is predictive analytics and statistical analysis. He holds a masters degree in Data Science and multiple Microsoft certifications covering SQL Server, Power BI, Azure Data Factory and related technologies.

Hristo Hristov is a Data Scientist and Power Platform engineer with more than 12 years of experience. Between 2009 and 2016 he was a web engineering consultant working on projects for local and international clients. Since 2017, he has been working for Atlas Copco Airpower in Flanders, Belgium where he has tackled successfully multiple end-to-end digital transformation challenges. His focus is delivering advanced solutions in the analytics domain with predominantly Azure cloud technologies and Python. Hristo's real passion is predictive analytics and statistical analysis. He holds a masters degree in Data Science and multiple Microsoft certifications covering SQL Server, Power BI, Azure Data Factory and related technologies.This author pledges the content of this article is based on professional experience and not AI generated.

View all my tips

Article Last Updated: 2022-06-10