By: Jared Westover | Updated: 2022-09-27 | Comments (5) | Related: > Transactions

Problem

Recently, a Microsoft SQL Server developer questioned my long-held advice of always using explicit transactions, at least when performing update statements, inserts, and deletes. I've preached for years that you should use them for almost any statement modifying a row for data integrity purposes. Before reconsidering, I would have argued for using them to update one row in a single table. He asked nicely, do you have to? After carefully considering it, I said no, you don't have to. This simple question made me reconsider why I advocate for explicit transactions.

Solution

In this SQL tutorial, I'll explore the primary situation where you want to use explicit transactions. We'll start by looking at what an explicit transaction is and how it differs from the default mode of auto-commit. By the end of this tip, I want you to make an informed decision on which one to use. Most importantly, start implementing the solution today.

SQL Transaction Modes

Brady Upton has a series of tips describing a database transaction as a unit of work performed against the database. SQL Server has three primary modes of transactions. Let's take a few minutes and look at two of them. I'm not going to explore implicit transactions. I'm also not going to compare performance differences between the two or edge use cases.

Auto-commit

By default, SQL Server uses auto-commit. With auto-commit, the end user doesn't need to issue any further commands to have a transaction committed. For example, in the SQL statement below, we create two simple tables and insert one row into each.

CREATE TABLE dbo.Checking

(

ID INT NOT NULL,

Amount DECIMAL(19, 2) NOT NULL,

ShortDescription NVARCHAR(100) NOT NULL,

TransactionDate DATE NOT NULL

);

GO

CREATE TABLE dbo.Savings

(

ID INT NOT NULL,

Amount DECIMAL(19, 2) NOT NULL,

ShortDescription NVARCHAR(100) NOT NULL,

TransactionDate DATE NOT NULL

);

GO

INSERT INTO dbo.Checking

(

ID,

Amount,

ShortDescription,

TransactionDate

)

VALUES

(1, 25.00, 'Starting my checking account', GETDATE());

INSERT INTO dbo.Savings

(

ID,

Amount,

ShortDescription,

TransactionDate

)

VALUES

(1, 100.00, 'Starting my savings account, Thanks dad!', GETDATE());

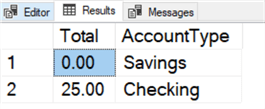

SELECT SUM(Amount) AS [Total], -- SELECT Statement

'Savings' AS [AccountType]

FROM dbo.Savings

UNION ALL

SELECT SUM(Amount) AS [Total],

'Checking' AS [AccountType]

FROM dbo.Checking;

GO

Auto-commit is about as simple as it gets. It's going to require the least amount of code. However, it does have drawbacks. The primary one we'll focus on here is if something goes wrong with the first insert statement and you don't want the second insert statement to execute, you're out of luck. Let's look at this in action. In the example below, I'm moving $100 from my savings account into my checking. See the following example:

INSERT INTO dbo.Savings

(

ID,

Amount,

ShortDescription,

TransactionDate

)

VALUES

(2, -100.00, 'Taking money out of my savings account.', GETDATE());

INSERT INTO dbo.Checking

(

ID,

Amount,

ShortDescription,

TransactionDate

)

VALUES

(2, 100.00, 'Taking money out of my account for a copy of a new NES game, sorry dad! I will replace it after I get a job.', GETDATE());

GO

Notice that the second insert SQL command will fail. I hope my savings account isn't missing $100. However, I would be wrong.

Now let's look at a way to work around this behavior.

Explicit Transaction in T-SQL

With explicit transactions, you tell SQL Server to start a transaction by issuing the BEGIN TRANSACTION syntax. Once your statement finishes, you can ROLLBACK or COMMIT. Ideally, you would wrap the transaction in a TRY...CATCH block. You can roll back the transaction and raise the exception if an error occurs.

If you don't want to deal with a TRY...CATCH, you can SET XACT_ABORT ON. This command is handy because it will roll back the transaction if an exception occurs. By default, XACT_ABORT is off.

Suppose you repeat the example from above by using an explicit transaction and XACT_ABORT. The entire transaction will roll back after the first exception occurs, which is the expected result. In my opinion, this is the primary reason to use explicit transactions.

SET XACT_ABORT ON;

BEGIN TRANSACTION; -- Begin Transaction Statement

INSERT INTO dbo.Savings

(

ID,

Amount,

ShortDescription,

TransactionDate

)

VALUES

(2, -100.00, 'Taking money out of my savings account.', GETDATE());

INSERT INTO dbo.Checking

(

ID,

Amount,

ShortDescription,

TransactionDate

)

VALUES

(2, 100.00, 'Taking money out of my account for a copy of a new NES games, sorry dad! I will replace it after I get a job.', GETDATE());

COMMIT TRANSACTION;

The money stays in my savings account until I shorten the message and make it to the store.

Now explicit transactions can have downsides. The first is if you don't want the behavior outlined above. Maybe you want the statements to continue and not roll back. The other would be if you have long-running transactions and are running into an issue with your transaction log filling up. Additionally, you must remember to add the COMMIT or ROLLBACK, or the transaction will run indefinitely. I'm sure you can list more, but these are the ones at the front of my mind.

Changing Guidelines

I developed the hard and fast rule of using explicit transactions like my dad's guidance when teaching me to drive. When I started driving, my dad would yell 10 and 2 when describing how to hold the steering wheel. He would constantly say stay two car lengths away from the car in front of you. I've been driving for decades and don't follow the 10 and 2 rule anymore. The rule is not wrong, but my arms are not comfortable on long drives.

Early on in my career, I worked with a DBA who would make developers use explicit transactions no matter what. He wasn't up for debates. Likely he had his reason for this. However, I would rather someone understand why to use explicit transactions instead of blindly following my advice. If I'm reviewing a developer's script that's performing an update on a single table, there's something in the back of my mind screaming add an explicit transaction. Still, I deal with the discomfort and move on from it.

During code reviews, explicit transactions are on my mind because I've created template scripts. I'll generally include the explicit syntax instead of having two separate templates. Perhaps I'm disappointed developers are ignoring my templates. However, maybe this means they are thinking for themselves, keeping what's useful, and disregarding what's not.

Conclusion

In this tip, we looked at two different modes of transactions. First, we reviewed auto-commit, which is the SQL Server default. We then turned our attention to explicit transactions. Explicit transactions can be used primarily to ensure multiple statements succeed or fail as one logical unit. In the comments below, I'm interested to hear some of your experiences advising on the type of transactions to use in SQL Server.

Next Steps

- Would you like a detailed overview of using transactions in SQL Server? Please check What does BEGIN TRAN, ROLLBACK TRAN, and COMMIT TRAN mean? by Brady Upton.

- In the article above, I mentioned that long-running transactions could cause the transaction log to grow excessively. Check out Long Running Transactions Cause SQL Server Transaction Log to Grow by Simon Liew for a detailed look into this behavior.

- Check out these additional resources:

About the author

Jared Westover is a passionate technology specialist at Crowe, helping to build data solutions. For the past two decades, he has focused on SQL Server, Azure, Power BI, and Oracle. Besides writing for MSSQLTips.com, he has published 12 Pluralsight courses about SQL Server and Reporting Services. Jared enjoys reading and spending time with his wife and three sons when he's not trying to make queries go faster.

Jared Westover is a passionate technology specialist at Crowe, helping to build data solutions. For the past two decades, he has focused on SQL Server, Azure, Power BI, and Oracle. Besides writing for MSSQLTips.com, he has published 12 Pluralsight courses about SQL Server and Reporting Services. Jared enjoys reading and spending time with his wife and three sons when he's not trying to make queries go faster.This author pledges the content of this article is based on professional experience and not AI generated.

View all my tips

Article Last Updated: 2022-09-27